Presicce-Acquarica is a municipality in the Leuca Cape established in May 2019.

The municipality is seventeen kilometres from Santa Maria di Leuca, the heel and end of the Italian peninsula.

With its imposing architectural works highlighting the Lecce stone, and its historical traditions, Presicce-Acquarica has become a place of illustrious screenplays and advertisements.

Let us now get to know the history and wealth of Presicce’s monuments, and then move on to discover Acquarica.

Presicce

Historical background

The Latin etymology of the term ‘Prae-situm-Prae-sitio’ supports the thesis of Giacomo Arditi, a historian from Presicce, that Presicce was founded in the 4th century A.D. following a long period of drought lasting three years, which forced the citizens of the neighbouring hamlets to occupy this once marshy area.

Others trace the origin of Presicce back to the presence of Basilian monks, who lived in nearby caves.

Important, but overlooked over the years, was the Byzantine domination, which anticipated the Norman one, which left significant imprints, from artistic value to customs and traditions.

From the 13th to the 19th century, Presicce saw the arrival of numerous feudal families, including the De Liguoro and Bartolotti families.

To the latter, the people of Presicce owe their retained nickname of ‘Mascarani’.

Prince Carlo Francesco Bartilotti, a greedy and pleasure-loving man, over the years won the ‘Jus primae noctis’, i.e. the right to share the first night with the young brides of the village.

It was probably this that led a masked man to shoot and kill the Prince.

Hence the people of Presicchio were branded for life with their nickname ‘I Mascarani’.

The Chiesa Matrice of Presicce and the column of Sant’Andrea

The “Chiesa Matrice” , dedicated to St Andrew and Mary Assumed into Heaven, was built in 1778, erected on the ruins of an ancient 16th century church.

This building is regarded as one of the most fascinating works in the province, and is a building with a clear late Baroque background, punctuated by pilasters of Corinthian order.

What remains of the old church is the ancient bell tower, also made of Lecce stone.

With its majestic dimensions, it is possible to see the church from various points in the city.

It has a Latin cross plan and, thanks to its openings at the top, has the advantage of being very bright, which allows for a fascinating play of colours throughout the day.

Inside, there are eight side altars enriched by stucco decorations and precious paintings on canvas by famous local authors such as Catalano.

The high altar, in rare polychrome marble, the baptismal font and the lustral stacks are of the Neapolitan school: thanks to recent reconstructions, it has been possible to identify the author in Baldassarre Di Lucca.

Even the angels and the bas-relief of the patron saint would seem to follow Di Lucca’s school (the Neapolitan school), so much so as to be attributed to the workshop of the famous sculptor Giuseppe Sammartino (author of the Veiled Christ).

Architectural exchanges between Presicce and Naples were probably also made possible by the affectionate friendship between Marquis Arditi and King Francis I of Bourbon.

Column of Sant’Andrea

According to some historical reconstructions, Prince Bartilotti, after marrying the baroness of Salve, moved to Presicce with his wife and first-born son.

At the age of just four, little Andrea died, which is why the prince had the column of Sant’Andrea Apostolo erected in memory of his dead son.

Hypogean Crushers

In the lower Salento region, the occupation of natural or artificial caves has been a real way of life for the locals.

In addition to living in them, however, in Presicce, they also created real places for processing olives and producing the Salento’s liquid gold, oil.

In 1816, there were some 23 underground oil mills, which had therefore, without knowing it, created a veritable underground city.

In autumn, with the olive harvest, work teams of about five men were created: three trappetari, a boy (turlicchiu) and a crew chief (nachiru).

Each ‘crew’ had two donkeys at their disposal that had to rotate the millstone.

For the entire autumn and winter, the trappetari worked day and night, sometimes even sacrificing Sunday.

The oil produced was largely sold, and ships departed from Gallipoli to distribute it throughout Europe.

I CURTI (courtyard houses)

In the historical centres of Salento, courtyard houses are widespread.

They consist of uncovered spaces around which several dwelling units with several entrances to the street were built.

This space, in which you can find a well, a pile, and in which animals were also once found, was shared by the different families living in the units. Examples are the Corciuli district, which is a very long courtyard with double access (from the Soronzi and Padreterno districts), characterised by a narrow alley.

Palazzo Ducale in Presicce with its hanging gardens

The ducal palace of Presicce, with its imposing construction, tells about a thousand years of history.

The structure organised over the centuries has followed the evolution of the baronial and princely lineages that have succeeded one another from the Securo to the De Specola, De Balzo, etc.

It is assumed that, as the Normans were a warlike people, a castrum was already present at that time to defend the first dwellings built at that time.

The roofs of the rooms inside the palace are generally made with barrel and angular vaults. One large room, known as the ‘throne room’, has a wooden truss roof.

It is also possible to identify the four historical phases in which the palace was built: the first is related to the medieval fortress; the second phase took place under the rule of the Gonzaga, Cito Moles and the Bartilotti family; the third was under the De Liguoro family, who began the renovation of the courtyard; and finally the fourth and last under Duke Paternò.

During this phase, the Duke decided to have neo-Gothic merlons introduced, in accordance with the eclectic fashion of the time, and to add new buildings, such as stables, warehouses and factories in the north wing of the palace.

Very important is the creation of the hanging gardens, a source of pride for the people of Presicchio.

The flowerbeds surround, in a symmetrical manner, an 18th-century fountain of mixtilinear shape, shaded by a lush wisteria. Thanks to its elevated position, the garden enjoys a privileged view of Piazza Villani, where it is possible to admire the Matrix Church, the column of Sant’Andrea and several noble buildings.

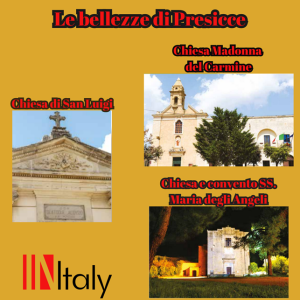

Other beauties of Presicce

Acquarica

The origin of Acquarica is very similar to the origin of Presicce; both were preferred because they were places with an abundance of water.

Some hypotheses suggest that Acquarica was inhabited from the 11th century onwards, when two settlements occurred: one in the castle area, the other in the Celsorizzo locality.

Other hypotheses predict that three hamlets existed around the centre of Acquarica: Cardigliano, Ceciovizzo (today Celsorizzo) and Pompignano.

The first two coexisted with Acquarica, while for Pompignano the history is slightly different.

Between the 9th and 11th centuries, the Saracens destroyed Pompignano and forced the inhabitants to find a new refuge, which they identified in Acquarica, given the abundance of water. Later, after the fall of the hamlets of Ceciovizzo and Cardigliano, their inhabitants came to swell the population of Acquarica, which in old maps is marked with the addition ‘de Lama’, which in Latin means lagoon, stagnation of water, from which the name of the district ‘Lama’ derives.

This backwater disappeared after the ‘vora’ formed, which swallowed up all the water, causing the area to dry up.

In the 12th century, Acquarica began to be ruled by Cavalier Guarino, who guaranteed its protection.

In the 15th century it returned under the hegemony of the Prince of Taranto.

In 1504 the Guarino family took over and held it until 1528 when they lost it for felony, having participated in the anti-Spanish revolt alongside the French.

From then on, Acquarica underwent a real decline in population and urban construction, which only ceased with the fall of the feudal lord Giovanni Centellas, who in the meantime had also renamed the town ‘Centellas’.

When his brief rule ceased, he resumed the name of Acquarica with the addition ‘del Capo’, to distinguish it from a hamlet of the same name in Vernole. In the 19th century, the local production of vessels made with reeds from the marshes of the Ionian coast became famous. This production was awarded a prize at the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873; from then on it began to be exported to Europe and beyond.

Acquarica Castle

The Acquarica Castle is par excellence the heart of the entire village, around which the entire hamlet developed.

Today, however, only part of the ancient fortress remains, with one of its four towers.

It is known as a medieval castle although, following various renovations in the 15th century, it took on a purely Renaissance appearance.

The castle was probably surrounded by a moat, which was partly filled in later: in fact, a document from 1688 mentions a ‘place called lo fosso de lo castello’ (the moat of the castle) and in 1821 the road behind the fortress (today’s Via G. Bruno) was still called ‘strada del fosso’ (the moat road). There are several heraldic coats of arms on the structure, from the Guarino to the coat of arms of the Centellas.

The surviving tower represents the military reinforcement phase of the structure, presumably dating back to the 16th century. The lower floor houses the reed museum.

The inner courtyard is overlooked by the palatine chapel dedicated to St Francis of Assisi. The Renaissance portal leads into a vaulted room on the walls of which several painted fragments can be seen, and the apsidal basin with paintings still concealed incorporated in the later masonry, evidence of the medieval prece – dente church. Recent restoration work has identified numerous tombs from various periods on the floor, which are currently being studied.

Church of St Charles

The Church of St. Charles, located in the square of the same name in front of the castle, was built in the 17th century by Fabrizio Guarino Junior following a miracle associated with Bishop De Rossi during a pastoral visit to the Diocese of Ugento in 1711. The baron, ill despite his wealth, asked the intercession of St Charles Borromeo and made a vow to build a church in his honour. His fever disappeared immediately, and after being cured, the baron built the church in front of his castle.

The bell tower is in an essential style, but the top is Baroque. Until the 1960s, the old clock tower stood next to the façade. A Latin epigraph from 1772, found among its remains, was placed outside the east wall of the building and reads: ‘The times that pass here are marked and the hours that pale death reaps fast to man. Year of the Redemption 1772’.

Inside, the church has a double nave. The left aisle is larger, consisting of three bays, with the stone high altar on the chancel. The right aisle is of uncertain origin, but it was built at least in 1664, when the altar of the Annunciation of Mary was erected. The original balustrade was removed after the Second Vatican Council and is now kept in the sacristy.

The left aisle has three altars: one dedicated to Madonna of the Rosary with a 17th century painting, one dedicated to St Charles in the 17th century in Baroque style, and one dedicated to the Immaculate Virgin with Rococo lines and three stone statues. There were three altars in the right aisle, but only the altar of the Annunciation, commissioned by Giovanni Antonio de Capo in 1664, remains.

Inside the church, there are several valuable artefacts, including those of the Patron Saint, the Immaculate Conception and the Madonna of the Rosary, which probably came from Naples and the Salento region, testifying to the relationship between the local patriciate and artistic influences from the capital.

Reed Museum

The museum in the Acquarica castle celebrates the ancient local craft tradition of working ‘paleddhu’, a type of marsh reed. This craft dates back to at least the 18th century and involved the harvesting of flexible rushes from wetlands in the Salento region, such as the marshes between Ugento and Salve and those of Acaya and Avetrana.

After harvesting, the rushes were treated by immersing them in boiling water and then air-dried to obtain a yellowish hue. The sulphur phase gave the rush colour and pliability, making it suitable for weaving. The ‘spurtare’, the skilled weavers, created everyday objects such as ricotta cheese baskets and ‘sporte’ for the olive harvest, as well as high-quality decorative items.

In the 19th century, ‘paleddhu’ weaving reached the pinnacle of success, with international recognition such as the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873. However, over time, the art of reed weaving declined and survived only marginally until the 1960s-70s, when only a few women still knew the art of ‘paleddhu’. Today, the activity is almost extinct, but some local companies continue to keep it alive by offering modern, innovatively designed objects made from ‘paleddhu’.

Other beauties of Acquarica

Feasts and celebrations in Presicce-Acquarica

Religious festivities in Presicce-Acquarica include celebrations in honour of the Madonna dei Panetti, San Luigi, the Madonna del Carmine, the Madonna del Ponte, San Carlo and Sant’Andrea. For the feast of San Carlo, the inhabitants used to raise a pig during the year, which roamed the streets eating leftovers offered by families. The pig was then slaughtered and sold to finance the festivities.

The feast of Saint Andrew in Presicce includes the tradition of the ‘focareddha’, a bonfire lit on the eve of the saint to warm up and celebrate the cold period that begins with Saint Andrew. This tradition has turned into a spectacle with religious and artistic moments, including fireworks.

Another tradition is ‘lu tamburreddhu’, in which musicians play traditional band tunes during the novena of Saint Andrew. This event involves the whole community and bonds are created between the citizens and the musicians.

The civil festivities include ‘Presicce in Mostra’, a summer event created in 1999 in which public and private cultural sites are opened to visits. These include churches, palaces, underground oil mills and gardens, accompanied by musical entertainment, theatre performances, tastings and historical re-enactments.

For information https://www.prolocopresicce.info/presicce-in-mostra/

Festive traditions are rooted in local history and offer moments of sharing and celebrating culture and festivities.

The ‘Sagra del Grano,’ now known as ‘Grano in Festa,’ is an event that originated in 1993 thanks to the Arci di Acquarica, which organised a party in a courtyard on Corso Matteotti to celebrate a documentary on wheat production. In 2006, the event was filmed and relocated to the fascinating Celsorizzo complex, characterised by its fortified tower and dovecote tower, with straw sculptures (made thanks to a twinning agreement with Croatia) scattered around the area.

For information https://prolocoacquarica.wixsite.com/prolocoacquarica

This event usually takes place on the last weekend of July or the first of August and includes the preparation of traditional dishes such as ‘lu ranu stumpatu’ (cooked wheat seasoned with sauce and ricotta forte). There are also concerts, markets, guided tours, conferences and courses in cooking and reed weaving.

‘Colori dell’olio’ is an event that started in 2009, initially as a festival dedicated to olive oil, a product that is representative of Presicce thanks to the tradition of underground oil mills and the local oil economy. This has contributed to Presicce becoming a ‘City of Oil.’ Initially held in Piazza del Popolo, the festival featured exhibitions of oil products by local companies and typical dishes, accompanied by evening musical performances.

Over the years, the event has evolved into a major music festival, always maintaining the culinary aspect. High-calibre artists such as Francesco De Gregori, Max Gazzè, Piero Pelù, Nek, Fabrizio Moro and Noemi have featured in several editions.

This year, the guests of the event to be held from 17 to 19 August will be Eugenio Bennato, Edoardo Bennato and Roberto Vecchioni.